Kenneth E Silver ââåmodes of Disclosure the Construction of Gay Identity and the Rise of Pop Art

Over the by xx years, scholarship on Robert Rauschenberg'due south early artistic development has been largely informed by the exhibition and monograph organized in 1991 by Walter Hopps for the Menil Collection in Houston. In the installation and its related catalogue, both titled Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s, Hopps closely examined the groundbreaking experimentation undertaken by Rauschenberg between 1949 and 1954, charting the emergence of the primary themes and motifs that would come up to ascertain the sixty-year arc of the artist's career. During that seminal menses, Rauschenberg established an ongoing interest in grasping the full range of art-making mediums, including printmaking, painting, photography, drawing, sculpture, and conceptual modes, frequently blurring chiselled distinctions past using multiple techniques and materials in combination. Mother of God (ca. 1950), office of an informal group of artworks that was included in his first solo exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in 1951, is a key example of the innovations Rauschenberg accomplished in those years. It is worth recounting here some of the details of the creative person'due south early biography in order to sympathize the origins and implicit meanings of Female parent of God.

Growing upwardly in the Gulf Declension town of Port Arthur, Texas—once habitation to the world's largest concentration of oil refineries—Rauschenberg had little exposure to art despite demonstrating a proclivity toward drawing.1 A decisive moment occurred during his service in the U.s. Navy (1944–45). While stationed in San Diego, he fabricated his get-go trip to an art museum, visiting the Huntington Library, Art Collections, and Botanical Gardens in San Marino, California, where he saw Thomas Gainsborough's The Blue Boy (ca. 1770) and Thomas Lawrence's Little finger (1794). Experiencing firsthand both the grandeur of this privately created museum and the impressive scale of the life-size portraits Henry E. Huntington nerveless, which as a child Rauschenberg had seen reproduced on his female parent's playing cards, he understood that becoming an artist could be a viable career choice.2 After his belch from the Navy in summer 1945 Rauschenberg settled briefly in Los Angeles, somewhen relocating to Kansas Urban center, Missouri, in January 1947. Subsequently that winter, encouraged by a friend, he enrolled at the Kansas City Art Institute on the GI Bill. The post-obit twelvemonth he did the de rigueur stint in Paris, studying at the Académie Julian, where he met his time to come married woman, beau artist Susan Weil (b. 1930). In fall 1948, Rauschenberg and Weil returned to the Usa and registered at Blackness Mountain College, almost Asheville, Northward Carolina, where they anticipated that Josef Albers (a former instructor at the Bauhaus whom Rauschenberg had read near that summertime in Time magazine) would instruct them in the unique approach to art making that the Bauhaus main termed "disciplined freedom."three Although Rauschenberg spent a full bookish twelvemonth at Blackness Mountain studying Albers's (1888–1976) do of working with the inherent backdrop of materials and their relationships to i some other, petty artwork is extant from this period.4

The two young artists soon grew weary of Albers's methodology and the isolation of country life at Black Mountain; afterwards the 1949 summertime session they moved to New York, finding inspiration in the city's thriving urbanity. Rauschenberg and Weil, a New York native, would live in the metropolis for ii years, during which time they married, had a son, and and so divorced. Together they frequented the vanguard galleries of Charles Egan, Samuel Kootz, and Betty Parsons, viewing the first generation of American postwar art and admiring in particular the freedom of the Abstract Expressionists. Exhibitions by Willem de Kooning (1904–1997) and Franz Kline (1910–1962) at Egan and Barnett Newman (1905–1970) and Clyfford Even so (1904–1980) at Parsons were especially revelatory. Equally Weil reminisced: "You made sure you saw everything and took it all in."5 Rauschenberg often brought along his photographic camera, photographing the shows he visited to aid his ain process of "taking it all in."6

In search of gratis studio infinite, Rauschenberg enrolled at the Art Students League, using his GI Neb benefits to cover the tuition and provide a living stipend. For three semesters he attended morning and evening classes in both life painting and painting limerick. Not particularly interested in the formal teachings of the League, yet, Rauschenberg used the classes to forge his own creative identity. Over the adjacent two years, he created a body of work grounded in his then naive understanding of what information technology meant to become an artist.seven The culmination of his labor was seen in the paintings—including Mother of God—that Rauschenberg presented at Betty Parsons Gallery in spring 1951. These works melded abstraction with imagist concerns, using everyday printed materials as collage elements and featuring representational components and evocative titles, characteristics that would become hallmarks of Rauschenberg's mature production.8 Whether reacting to, imitating, or synthesizing the abstract trends and so prevalent in American art, Rauschenberg after recognized how essential this menstruum had been to his development: "I couldn't really emulate something I was so in awe of. I saw Pollock and all that other work, and I said, Okay, I tin't go that way. Information technology's possible that I discovered my own originality through a series of cocky-imposed detours."ix

2. Installation view of Jackson Pollock, Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, November 26–Dec 15, 1951. Photo: Robert Rauschenberg, courtesy the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed past VAGA, New York, NY; Pictured artworks: © The Pollock-Krasner Foundation / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

The genesis of the Parsons exhibition may be considered either beginner'southward luck or an astute acknowledgment of Rauschenberg's precociousness. He was just twenty-five years former and completely unknown on the New York art scene when he approached the gallerist. Weil recalled that Rauschenberg felt comfortable contacting Parsons because she herself was an artist.10 This memory dovetails with Rauschenberg's own story that he had merely been looking for a critique of his work. Parsons after recalled her prescient impressions of that run into: "The moment I met Bob, I could tell he was alive, perceptive and aware of everything that was going on. . . . Of course, looking at those early pictures I knew he still had a long way to go. Only I sensed that spark—I knew that there was a big talent there. All that was needed was encouragement and time for that talent to develop."11 And so the grande matriarch of the New York gallery earth centered on Fifty-Seventh Street, Parsons represented major artists such as Newman, Notwithstanding, Jackson Pollock (1912–1956; fig. ii), and Mark Rothko (1903–1970), notwithstanding she unexpectedly offered Rauschenberg a show based on the works he carried into the gallery that afternoon. She selected the pictures for the exhibition, however, on a follow-up visit to Rauschenberg'due south apartment/studio with Nonetheless. Perhaps the presence of such an eminent and stern Abstruse Expressionist standing in his studio unnerved Rauschenberg; post-obit the visit he repainted some of the works Parsons had selected, thereby "improving" them. Information technology is unknown whether Female parent of God was one of the works Rauschenberg sensed needed comeback.

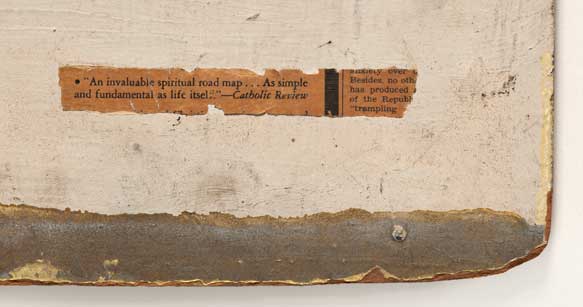

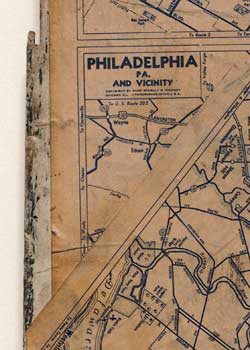

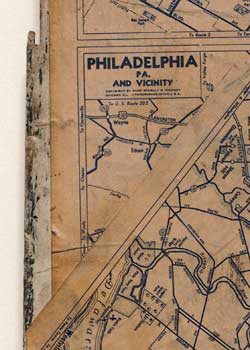

Female parent of God is composed of sections of eighteen urban center maps that take been cut (and in some instances torn) from Rand McNally & Company road atlases.12 The cities and regions represented include Baltimore; Birmingham; Boston; Buffalo; Camden, New Bailiwick of jersey; Cleveland and other areas of northeastern Ohio; Council Bluffs, Iowa, along the Nebraska border; Dallas; Dayton, Ohio; Denver; Detroit; Fredericksburg, Virginia; portions of Glendale, Pasadena, and Whittier, California; Minneapolis–Saint Paul; Montreal, Quebec; New Orleans; Oakland, California; northwestern Oregon; western Pennsylvania; Philadelphia; Pittsburgh; Riverside, Ottawa; Saint Louis; Salt Lake City; San Antonio; Seattle; Toledo; areas of southeastern Virginia; and Washington, D.C. Rauschenberg applied these fragments to a Masonite panel in an occasionally overlapping collage, leaving a big, open up circle at the center of the work that he painted white. Covering approximately two-thirds of the painting's surface, this circular course dominates the composition, which is otherwise divided into 3 zones. The lower third of the painting is left unadorned past collage elements and has also been painted white. The bottom of the picture is anchored past a thin bar (1-one/8 inches at its widest) of silver paint, its one time brilliant sheen now dulled. To the extreme right, floating in the painted area two inches above this metal stripe, is a fragment (4 one/16 inches wide) from a newspaper bearing the words, "'An invaluable spiritual road map . . . As elementary and cardinal equally life itself'—Catholic Review" (fig. 3). Bold vertical lines split this tagline from a second printed fragment that reads: "anxiety over / Too, no oth[er] / has produced / of the Repub[lic] / 'trampling."13 Within the maps themselves, dumbo grids and networks of curving lines appear to class a kind of passe-partout for the fundamental painted class. Rauschenberg used two unlike atlases published past Rand McNally, as evidenced by the varying typography. The bulk of the maps are printed in a boldface font in nighttime blue ink on heavy-grade white paper, at present faded yellowish, whereas others are printed in a regular-weight font in light blueish ink on a lighter form paper that is less faded (fig. 4).14 Rauschenberg has broken the printed grid of the maps by pasting the diverse fragments upright, upside down, and/or sideways. This random orientation lends an overall graphic quality to the painting that respects the grid pattern equally an organizing device, a feature of much of Rauschenberg'southward art.

4. Particular of Robert Rauschenberg's Female parent of God showing variations in map types

5. Detail of Robert Rauschenberg's Mother of God showing layering of paint and maps

4. Particular of Robert Rauschenberg's Mother of God showing variations in map types

The edges of the Masonite panel that supports the painting are now frayed (fig. 5), and the painted areas, executed in various shades of white, have been yellowed by time. In the early 1950s Rauschenberg used both traditional oils and business firm paint, which was more than readily bachelor; here this has resulted in variation between glossy and matte areas in the painted surface. Brushstrokes of unlike angles are visible in the circular form and the painted zone below the collage, articulating the painting's surface texture and revealing traces of the artist's hand. Similarly, in the painted section at the lesser of the panel, i sees what appear to exist nighttime, soiled areas along both the left and right edges. Closer inspection reveals that these are palm prints, probably belonging to the artist. Visual examination too reveals that Rauschenberg applied the paint in several campaigns earlier and after affixing the maps; one can discern collage elements both on top of and underneath the pigment layers. At the indicate where the painted circular course meets the corners of the printed maps, Rauschenberg has alternately revealed and hidden the contours of the paper. Along the bottom of the circle, collaged maps of Detroit and Dayton creep in, extending approximately one inch under the pigment. Immediately in a higher place, where the circular course curves right, a torn fragment of Cleveland encroaches even more deeply, stretching approximately four i/16 x 7 ane/two inches (at its widest) beneath the painted surface. Overall, Rauschenberg has pasted the maps in a conscientious even so not necessarily seamless manner; his sense of precision is sometimes forsaken in the interest of developing the painting'due south content. One tin discern the possible presence of a painting underneath the maps. This is specially evident along the centre of the left edge (below a fractional map of Philadelphia) and along the lesser of the right border (underneath fragments of Glendale, Pasadena, and Whittier), where black paint is visible below the white. Mother of God has not been x-rayed, nor has it been analyzed using infrared photography. The reverse of the Masonite console provides scant testify, simply 2 isolated areas of green pigment on the top and left edges suggest the presence of a 2d painting beneath the visible work. Information technology is in keeping with what is known about other Parsons-era Rauschenberg paintings to assume that this moving picture may have been painted on top of an existing epitome or on the reverse of some other work.xv

Mother of God, like a number of the paintings included in Rauschenberg's premiere exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery, contains clear references to Christianity. Still it also embraces more broadly the notion of a spiritual journeying. Rauschenberg's associative mind construed urbanity as part of nature rather than a realm apart from it; hither the twisting and winding lines of city streets represented in the maps seem to articulate an organic pattern. The proliferation of road maps surveying urban landscapes foreshadowed a project Rauschenberg conceptualized at Blackness Mount in which he envisioned photographing the United States "inch by inch" on a journey across the country.16 This blazon of progressive mapping finds a parallel in Rauschenberg's noted engagement with seriality, a theme to which he would return repeatedly.17 For Hopps, the notion of traveling "resonated synchronistically with the Beat out generation's mix of seriousness and wildness, spirituality and play, besides as their explicitly American wanderlust."eighteen Other art historians may read the "traveling" theme equally a coded homosexual trope for "coming out."19 While it is true that Rauschenberg's personal life was undergoing significant and life-altering changes at the time Mother of God was created (i.east., coming together and partnering with Cy Twombly (1928–2011); the nascence of Rauschenberg'southward son Christopher; and the subsequent dissolution of his union to Weil), this author cautions against a queer studies interpretation. More than likely, the artist was of a mind to gloat birth and rebirth—thus the centrality of a round form alluding to pregnancy. Furthermore, Rauschenberg frequently employed round forms as compositional elements in the Parsons-era paintings and continued to utilize them in his later works. Throughout his oeuvre, motifs such as open umbrellas, bicycle wheels, tires, and clocks—whether in photographs and paintings or as actual objects—are familiar features.twenty Iconographically speaking, the circular course in Mother of God may just as aptly be understood equally a brightly shining lord's day or a planet or moon hovering higher up a horizon. Such otherworldly symbolism, paired with the anchoring furnishings of the collaged urban grid, amplifies the religious overtones suggested by the Catholic Review epigraph. A strictly terrestrial—yet equally plausible—estimation might be that the maps were intended to insinuate to life's journey or, in a more personal reading, to represent Rauschenberg's dreams of a well-traveled life for his newborn son.

Simply every bit the collage elements build upwardly the painting's surface, multiple layers of innuendo may be identified in Mother of God. A fundamental dichotomy exists between a visual reading that is based in the tensions between nature and the urban landscape and the title's unvarnished religious reference to Mary, Mother of God. Further substantiation for reading the round orb equally fecund may be establish in the prayer for the intercession of the Virgin Mary: "Blessed are y'all amidst women and blest is the fruit of your womb." Yet a secular reading of the title is also at play. When one encounters an unbelievable outcome, an exclamation of either surprise or astonishment, particularly in the American South, is "Sweet Jesus, mother of God!" These kinds of vernacular references take e'er been primal to Rauschenberg's thinking. As Hopps once noted, making his own religious pun: "Look at where he does accept titles, where words are used . . . accept them equally concretely as images. Word play and the nature of language and words are very important to him. Wherever at that place are titles, they are not incidental. They're christenings."21

Rauschenberg'south family unit belonged to the Church of Christ, and his mother, Dora, in particular, was deeply religious. He spent every Sunday in church and Sunday school and attended Bible report classes each summertime. When Rauschenberg was thirteen he believed he would become a preacher, but he decided against information technology when he realized that his family'southward fundamentalist denomination forbade dancing, one of his personal passions. Nonetheless, he did not entirely renounce his religious upbringing or his sense of duty to the church.22 Returning from Paris in early fall 1948, Rauschenberg visited his family in Lafayette, Louisiana, before enrolling at Black Mountain, and offered to paint a scene for the baptistery at the newly constructed Oaklawn Church of Christ. During his early years in New York, he continued to attend services of unlike religions.23 Although Rauschenberg ultimately replaced his adherence to organized religion with a broader conventionalities in the potential of humankind, during this determinative period in New York he—perhaps naively, perhaps earnestly—allowed the religious convictions embedded from his childhood to boss the subject affair of his work. He afterward characterized the Parsons-era paintings equally the products of a "short lived religious period" in which colour ("yellowish was life") assumed symbolic proportions.24 Indeed, many of the works in the Parsons exhibition were composed of passages of white, black, yellow, and silver. In Christian iconography, white can symbolize the Creator; black, righteous judgment; yellow, the glory of God; and silver, the price paid for redemption. The question of whether Rauschenberg was well versed in biblical symbolism remains unanswered; perhaps he was equally influenced by popular associations made with these colors, linking white with purity, blackness with force, yellow with happiness, and argent with persistence. Such a framework positions the palette of these works as a far more optimistic reflection of the artist'due south changing life. In a 1985 article on the Parsons-era paintings, Roni Feinstein offers yet another reading of this color scheme, writing of Female parent of God (which was then untitled) in particular: "Rauschenberg's painting may even so be seen every bit his personal estimation of ideas expressed in the spiritually oriented piece of work of Rothko, Newman, and other Color-Field painters. Once again, he transformed the principles involved in their art into something very literal. Rather than presenting a 'mythic orb' floating against the 'universal void,' he offered a flatly painted circle set against a grid of roadmaps. The specificity of place asserted by the roadmaps cancels the effect of infinity and the sense of boundlessness sought past his elders. . . . Whatever the artist'due south original intentions might have been, Rauschenberg'south untitled painting is revealing in a number of ways. Information technology demonstrates, over again, his literal-mindedness, his interest in locating his work—in both its subject affair and materials—in the real globe (and, equally is significant to his later art, in America), and his empathic not-illusionism."25

6. Robert Rauschenberg, Untitled (Night Blooming), ca. 1951. Oil, asphaltum, and gravel on canvass, 82 1/two x 38 3/8 in. (209.half-dozen ten 97.five cm). Robert Rauschenberg Foundation; © Robert Rauschenberg Foundation / Licensed by VAGA, New York, NY

Rauschenberg returned to Black Mountain in tardily summertime 1951. His Dark Blooming serial (fig. 6), the first paintings he fabricated after reenrolling, featured richly worked surfaces he created past roofing his canvases with blackness paint and tar and laying them facedown on the ground while moisture to attract dirt, gravel, and other debris.26 This series apace gave way to a grouping of entirely different pictures, which, while wholly abstruse, extended his interest in spiritual themes and references. The importance that these works, known as the White Paintings (1951), held for Rauschenberg is conspicuously evidenced in an impassioned letter of the alphabet he wrote to Parsons, pleading with her to exhibit them as before long as possible. His clarification of the paintings is especially illuminating: "They are large white (1 white as one God) canvases organized and selected with the feel of time and presented with the innocence of a Virgin."27 Rauschenberg'due south artistic evolution oftentimes built from 1 serial of works to the next, making information technology plausible to have Mother of God as prefiguring the more radical White Paintings. Branden W. Joseph has observed that "past keeping collage from the heart of the painting [in Mother of God], Rauschenberg . . . signified that the white was at once in the world and to be understood as somehow dissever from it. The white would thereby seem to be symbolic of the divine, with Rauschenberg presenting painting equally the consequence of a sort of incarnation. Like the body of the Virgin Mary, Rauschenberg's Mother of God serves as a material or bodily vessel for the manifestation of the divine. Rauschenberg'southward collaging of a paper clipping from the Catholic Review to the lesser correct corner only reinforced the connection."28 The direct association between God and the color white made past Rauschenberg in the same letter to Parsons furthers such an interpretation, and, however ironically given that the creative person was focused on charting a new class in his personal life at the time the work was created, his use of map fragments as a "spiritual roadmap" is unaffected.29

Although Female parent of God may be rooted in a kind of personal expressionism that Rauschenberg interpreted abstractly, the imagist attributes of the collage elements were an equally strong force in shaping the work'south composition and subject matter. Collage—whether it involved pasting, assemblage, or transferring—would become i of Rauschenberg's nearly important artistic tools, one he would employ consistently throughout his career. His epitome bank was impressively large and encompassed fine art historical imagery, pop culture, and items from everyday life that he captured with his camera and paired in unexpected juxtapositions. The materiality of the image (and, especially in later works, the object) was paramount to his creative process. Joseph has observed that in Mother of God , "emphasizing materiality through collage was one ways of opposing the transcendent status of the prototype."30 Over the years much has been made of the relationship between Rauschenberg's piece of work and cubist collage practices. Rosalind Krauss put forth that the creative person heroically transformed the Cubist model, establishing "a grade of collage that was largely reinvented, such that in Rauschenberg's hands the meaning and role of the collage elements bore little relation to their earlier use in the work of [either] Schwitters or the Cubists."31 Feinstein quite rightly noted that "Cubist collage provided Rauschenberg with both his form and his means. For him, Cubism was a 'given' to be used and manipulated at will. He exploited Cubism's gridded and rectangular structure, its bitty nature, and the fact that collage was a conclusion-making process. He used collage as a vehicle for content and as a metaphor for consciousness."32 Rauschenberg, however, has downplayed the impact that formal aspects of Cubist collage had on his work.33 Instead, he has traced his use of the technique to his childhood, when his female parent modeled a variety of collage processes through her work with scraps of material. Known as an peculiarly frugal seamstress, Dora was the talk of Port Arthur for her ability to arrange her patterns and so tightly that she used every inch of cloth.34 Rauschenberg recalled witnessing the creation of his mother's patchwork quilts as a child. "That's where I learned collage," he once remarked, and knowing his background, information technology is not hard to take her case as his primary source.35 Indeed, the inherent and intuitive have always taken precedence over the formal and the learned in Rauschenberg'south art.

Rauschenberg's exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery opened on May 14, 1951, and, equally was standard for the fourth dimension, remained on view for merely three short weeks.36 The presentation consisted of thirteen easel-size oils in the smaller gallery while the larger main room featured works by Walter Tandy Murch, an creative person known for his realistic depictions of mechanical objects and illustrations for such magazines as Forbes and Scientific American. "He was in the A string gallery and I was in the B string gallery," Rauschenberg recalled, humorously acknowledging the art world'southward hierarchy.37 The titles of many of Rauschenberg's paintings followed the abstruse expressionist convention of numbering (i.e., No. 1, No. two, and then on, up to No. v), while others included poetic phrasing, such as 22 t he Lily White (ca. 1950) and Should Beloved Come First? (ca. 1951). Several others incorporated religious references, including Crucifixion and Reflection (ca. 1950), Mother of God, Trinity, The Man with Two Souls (1950), and Eden (ca. 1950). Many of the exhibited works had not been made at the Art Students League just rather in Rauschenberg'due south apartment/studio, where they were created, as Weil relates, "right in the apartment. Started and finished there."38 4 paintings (No. half-dozen, 1951; No. 7, 1951; Stone, Stone, Stone [ca. 1951]; and Should Love Come First?) appear as handwritten additions to the printed checklist, indicating that they were bachelor for sale but peradventure had not been installed on the gallery's walls. The listings for some other three works (No. eight, 1951; No. ix, 1951; and No. ten, 1951) in a recently located Parsons ledger book suggest that they were delivered to the gallery for consignment after the exhibition opened. Thus, there may accept been as many as twenty paintings in the gallery at 1 time. Their prices ranged from $150 to $750, with most works priced in the $400 to $500 range.39

Four days after the exhibition airtight, Parsons submitted her expenses for the advertising, announcements, and postage (for a total of $121.10) to Rauschenberg, noting that in that location had been no sales. She spent $71 to advertise the show in two dailies (the New York Times and Herald Tribune) and one monthly mag (ARTn ews), an investment that generated three curt reviews.40 Two of the reviews were thing-of-fact, preferring to describe the works rather than annotate on their execution or effectiveness. Dorothy Gees Seckler best-selling the youthful nature of the work, characterizing information technology as "naively inscribed with a wavering and whimsical geometry."41 Stuart Preston, in keeping with his usual curmudgeonly style, was more pointed. While conceding that the paintings were visually compelling, "stylish doodles in black and white and liberal helpings of silver pigment," he however believed them to be ill conceived, concluding that they were a "spawning footing for ideas rather than finished conceptions."42

Today it is hard to imagine what some of the Parsons-era paintings may have looked like; the reviews offer scant evidence, no installation photography has been located, and the artist kept no records from that fourth dimension. Photographs by Aaron Siskind (1903–1991) document four works (Eden; Trinity; Stone, Stone, Stone; and Should Honey Come First?) that take since been either painted over, lost, or destroyed.43 When the exhibition closed, Rauschenberg was faced with the trouble of storage. Merely those works that he could fit into his motorcar were saved; he divided them between friends, including artists Sari Dienes (1898–1992) and Knox Martin (b. 1923), and stored others at his in-laws' summertime home on Outer Island, Connecticut (the works kept in that location were lost the side by side summer in a fire). The remaining paintings were broken up and left with the trash in the basement of the gallery. Of the twenty works exhibited or offered for sale in connection with the show, just five are extant today: Crucifixion and Reflection, Mother of God, 22 t he Lily White, The Man with Ii Souls,44 and Untitled [with collage and mirror] (ca. 1951).45 Iii others—No. 1, 1951; Should Love Come First?; and No. 10, 1951—were later repainted black.46 The Parsons ledger book indicates that iii pieces were left on consignment longer than previously known: Pharaoh and No. vi, 1951 remained at the gallery until September 13, 1951, and No. viii, 1951 (the highest priced picture at $750) was returned to the artist on Dec 12, 1951.

Reflecting on the Parsons exhibition, Rauschenberg was unusually self-critical, admitting "how completely indulgent" he had been when he started painting.47 He acknowledged that the works were youthful attempts at producing "allegorical cartoons, using abstract forms." Painted mostly in "blackness, white and yellowish [and silvery] . . . they were very simple-minded paintings."48 However, his sense of experimentation was evident from the outset: "The beginning one that I used mirrors in was in the Betty Parsons show . . . and then that the room would go part of the painting. I didn't even know what I was doing. Now I can rationalize it. . . . I did crazy things in those early Betty Parsons days—similar cutting off my hair and putting it backside plastic and gluing information technology in."49

Although none of the paintings sold (perhaps non surprisingly given that they were created by a novice and Parsons generally did not have a great rail record for sales), Rauschenberg's work registered with fellow artists, and the evidence led to several of import friendships. The exhibition besides prompted Jack Tworkov and Leo Castelli to ask Rauschenberg to participate in their exhibition Today'southward Self-Styled Schoolhouse of New York, commonly known as the "Ninth Street Show" in reference to its venue, the outset floor and basement of a building on East Ninth Street that was slated for sabotage. 22 t he Lily White was removed early from the Parsons exhibition for inclusion, a fact that surely accounts for its consistent presence in Rauschenberg'south exhibition history. Nearly significantly, John Cage (1912–1992) visited the Parsons exhibition and, intrigued by the works, somehow finagled No. 1, 1951 every bit a gift, conveniently announcing, "the price doesn't affair since I have no money."fifty At the end of 1951, Rauschenberg was invited to join the Artists' Order established in 1949 past the and so-called Downtown Group of artists and so working in Lower Manhattan. Despite the fact that this honor was bestowed on him ahead of other artists of his generation, such as Alfred Leslie (b. 1927) and Larry Rivers (1923–2002), Rauschenberg was never interested in condign a member.

When Rauschenberg returned to Black Mountain in 1951, he left Female parent of God and several other works with his friend Knox Martin for safekeeping. Information technology is unknown when or nether what circumstances Rauschenberg reacquired the painting. Martin maintains that he held on to the work for several decades before selling it to Castelli.51 By 1980, the offset yr for which records exist in the artist's archives, Female parent of God is noted as belonging to the creative person and being stored in New York. The first published reference to the motion picture appears in Seckler's review of the Parsons testify, which notes that in some of the works "collage is introduced, either to provide textual effects—every bit in the picture whose background is made entirely of road maps—or to suggest a very tenuous associational content."52 The work was known simply as Untitled until the title Female parent of God was (re)attached to it by Hopps, who in the grade of his research for Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s showed the artist images of his piece of work and asked him to match them to the Parsons checklist. When Hopps read the title Mother of God, Rauschenberg replied in no uncertain terms: "Had to be a circle. For some strange reason, I remember that information technology could be that i," and pointed to a photograph of the painting, which was then known every bit Untitled [Road Maps].53

Xl years passed betwixt the first presentation of Female parent of God at Betty Parsons Gallery in 1951 and its next public showing, in Hopps'southward 1991 exhibition, which opened at the Corcoran Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. The painting appeared publicly three more than times in the 1990s. It was side by side included in the exhibition Trounce Culture and the New America: 1950–1965, which was organized by the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York and traveled to Minneapolis and San Francisco between 1995 and 1996. The following twelvemonth, it was included in the creative person'due south third retrospective, which toured four museums in America and Europe from 1997 to 1999. As the decade airtight, Mother of God entered the collection of the San Francisco Museum of Mod Fine art as part of an unprecedented conquering that also included 15 works (ane of them a promised souvenir), all purchased straight from the artist. The painting was first shown at the museum in 1999 in an exhibition highlighting these acquisitions. It was next exhibited in Treasures of Modern Art: The Legacy of Phyllis Wattis at SFMOMA in 2003, and and so in a permanent drove presentation from 2006 to 2007. Most recently it was included in the celebratory exhibition 75 Years of Looking Forward: The Ceremony Prove in 2009–10; Feinstein contributed a general text on all of the museum's Rauschenberg acquisitions to the accompanying catalogue.54

As noted at the opening of this essay, in heralding Rauschenberg'due south work from the early on 1950s as a demonstration of the creative person's precocious inventiveness, Hopps's 1991 exhibition contributed greatly to establishing the significance of the years 1949 to 1954 to the artist's hereafter artwork. The evidence'due south impact was underscored by the reactions of art critics. In response to the exhibition'due south debut in Washington, D.C., one reviewer associated Mother of God in particular with the piece of work of artists, poets, and musicians of the Beat generation, of which Rauschenberg had not been an agile member: "The gentle irony hither gives an inkling of the Beat sensibility. Kerouac'due south On the Route wasn't published until 1957, well-nigh of it was written between 1948 and 1951, and Rauschenberg'due south Mother of God is its visual equivalent."55 In a joint review of the Hopps exhibition and a concurrent presentation staged at the National Gallery of Art as the finale for his ROCI (Rauschenberg Overseas Culture Interchange) project, New York Times fine art critic Roberta Smith drew parallels between the artist's early use of photographs, newsprint, and other printed paper and the treatment of these materials in his later on, large-scale works. Referring to Mother of God, she wrote: "Ane of the about absorbing works in this starting time gallery is a crude white sphere painted on a background fabricated of cheap blue-and-white city maps. . . . Titled Mother of God, this painting exudes an antique, pre-cartographic charm and a non-Western mysticism, merely information technology also hints at global ambition."56

Indeed, as his art and career developed, Rauschenberg took full measure of the world, incorporating images—mostly his own photographs—from around the globe into his expanding repertoire. Both as an creative person and equally a person, he knew few boundaries, and his artistic vision invariably evinced optimism, hope, and humour, while at the aforementioned time sustaining serious insight into the human condition. When the Hopps exhibition traveled to Chicago in 1992, one reviewer noted these qualities in Mother of God, writing: "Information technology is a mensurate of this piece of work'south complexity that the [Catholic Review] quote seems to function simultaneously as an ironic joke and equally an utterly sincere bulletin. On the one hand, it's hard to see what sense fifty-fifty the least demanding and least literal traveler might make of this collision of map fragments, to say zilch of the empty circle that aggressively cuts off each map and dominates the viewer's attention. And yet in his juxtaposition of maps and circle Rauschenberg appears to be making a pretty clear statement—to exist drawing, particularly in calorie-free of his later work, his own 'spiritual road map.' "57 The road map the artist followed while executing Mother of God certainly served him well, charting an approach to art making that in its spirit of invention clearly distinguished him among his peers.

Notes

- Rauschenberg's art practice was more than intuitive than studied. Although he may have filled his childhood notebooks with drawings and was known to sketch portraits of his boyfriend enlisted men while in the Navy, his mature artistic activity included very little line drawing per se. He rarely drew (with the exception of body tracings, equally in Lawn Combed [ca. 1954] or Wager [1957–59]; or to work out the assemblage of some of his more complicated Combines, such as Monogram [1955–59]; or for works that include technological and/or mechanical elements, such as Oracle [1962–65]). Leo Steinberg, discussing Erased de Kooning Cartoon (1953), has stated that "fifty-fifty in 1953, [Rauschenberg] sensed where he was heading—toward a visual art that had no further use for the genius of drawing." Run into Leo Steinberg, Encounters with Rauschenberg: A Lavishly Illustrated Lecture (Houston: Menil Foundation, 2000), 20.

- The biographical details in this essay are fatigued from research conducted for the exhibition Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective and the accompanying catalogue, which contains an extensive chronology. See Joan Young with Susan Davidson, "Chronology," in Robert Rauschenberg: A Retrospective, ed. Walter Hopps and Susan Davidson (New York: Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1997), 550–87.

- For more on Albers's teaching methods and Rauschenberg's response to them, see Martin Duberman, Black Mountain: An Exploration in Community (New York: Due west. West. Norton, 1993), 55–56 and 459–60n51.

- The iii extant works executed at Black Mount during the 1948–49 academic twelvemonth are the woodcut This Is the First Half of a Impress Designed to Be in Passing Time (ca. 1949) and 2 photographs, Untitled (Interior of an Old Carriage) (1949) and Repose House—Black Mount (1949).

- Weil had a physical reaction: "And so we walked in [Egan Gallery], and Franz Kline was on the wall, and I remember putting on the lite, and y'all just felt like you'd been HIT in the breadbasket by these paintings." See Susan Weil, unpublished interview with Walter Hopps, January 15, 1991, New York. Kline had two exhibitions at Egan Gallery (October 16–November 4, 1950, and November–December 15, 1951). Rauschenberg, on the other paw, had a cognitive reaction: "But I was in awe of the painters; I mean I was new in New York, and I idea the painting that was going on here was just unbelievable. . . . I was decorated trying to observe means where the imagery and the fabric and the meanings of the painting would be not an illustration of my will. . . . There was a whole language that I could never make function for myself in relationship to painting and that was attitudes like tortured, struggle, hurting . . . but I never could meet those qualities in pigment." See Robert Rauschenberg, Oral History Interview conducted by Dorothy Gees Seckler, Dec 21, 1965, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C. Accessed June 23, 2013. https://www.aaa.si.edu/collections/interviews/oral-history-interview-robert-rauschenberg-12870#transcript.

- For example, Rauschenberg took photographs of Pollock'due south last exhibition at Betty Parsons Gallery (Nov 26–December 15, 1951) in improver to photographing diverse exhibitions at the Stable Gallery, including his own (September 15–October three, 1953), the Annuals (1953–55), Alberto Burri (Nov 23–December 12, 1953), and one as yet unidentified bear witness. I am grateful to Megan Fontanella, associate curator, Collections and Provenance, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York, for her confirmation of the 1953 Burri exhibition. Contact proof sheets in the athenaeum of the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation document the artist's early photography. Run into also Nicholas Cullinan, Robert Rauschenberg: Photographs 1949–1962, ed. Susan Davidson and David White (New York: Distributed Art Publishers, 2011).

- Susan Weil has remarked on Rauschenberg's lack of sophistication at this appointment, stating recently that ". . . when Bob came to Blackness Mount, he hardly knew what a painting was. . . . I hateful, he had been to school in Kansas City, and he knew a niggling scrap and so, simply he was very naive about art . . ." Encounter Susan Weil, Oral History Interview conducted by Karen Thomas, Jan five, 2011; re-create in the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation archives.

- Imagism equally evidenced in Rauschenberg's piece of work is defined past Hopps as a "manner of fine art-making where specific representations and iconographically recognizable images are employed as disparate elements within the fine art. These disparate elements may appear as rendered images or be included as collage or assembled additions of 'plant objects.'" See Walter Hopps, Robert Rauschenberg: The Early 1950s (Houston: Menil Foundation and Houston Fine Art Printing, 1991), 12.

- Robert Rauschenberg quoted in Calvin Tomkins, Off the Wall: A Portrait of Robert Rauschenberg (New York: Picador, 2005), 58.

- Weil, unpublished interview with Hopps, January xv, 1991.

- Betty Parsons quoted in John Gruen, "Robert Rauschenberg: An Audience of One," ARTnews 76, no. ii (February 1977): 47.

- The atlases can definitively exist identified as Rand McNally & Company publications past the copyright statement that appears beneath each city name: "Copyright by Rand McNally & Visitor/Printed in Chicago, Sick. Lithographed in the UsaA." Although it has non been possible to determine their exact publication dates, the Newberry Library, which holds the Rand McNally & Visitor papers, confirms that the maps used in Female parent of God are from atlases published between 1949 and 1956. The lettering used to label Logan Airport every bit information technology appears in the collage began with the 1949 edition, and 1956 was the final edition in which city maps were printed merely in blue; after 1956 Rand McNally began using more than colors. Correspondence with Daniel Fink, stacks coordinator, Roger and Julie Baskes Department of Special Collections, Newberry Library, Chicago, electronic mail to SFMOMA Publications Department, February 27, 2013. The painting is dated ca. 1950 because it was shown at Betty Parsons Gallery, New York, in May 1951, and therefore must accept been completed one-time between 1949 and early 1951.

- This second and bitty text has received little acknowledgment in the literature. Although the text is incomplete, information technology is interesting to note that these random words capture much of the anxiety and political pathos and so in evidence among abstruse expressionist artists. It has not been possible to identify the source of the clipping or to learn precise details virtually the Catholic Review publication.

- The maps printed on lighter-course paper are located along the work's lesser equally consummate map sections. At the far right edge and moving up is another expanse of lighter-grade newspaper. This section is more than torn and fragmented than those on the heavier-course paper, and it makes up the most complex areas of layering.

- For example, Crucifixion and Reflection (ca. 1950) is painted on the contrary of a signboard depicting circus horses, and Untitled [with collage and mirror] (ca. 1951) may have been painted on top of 1 of Weil'southward unfinished canvases. See Robert Rauschenberg, unpublished interview with Walter Hopps, et al., Dec 1985, the Menil Collection, Houston; transcript in the Menil Collection'south Conservation files. X-radiography recently conducted on No. 10, 1951 (now known equally Untitled [Nighttime Blooming series], ca. 1951) revealed an unidentified underlying image, executed primarily in yellows and whites. Brad Epley, email to the author, June 19, 2013. Run into besides notes 26 and 46.

- The projection was never realized. See Robert Rauschenberg quoted in Alain Sayag, "Interview with Robert Rauschenberg," in Robert Rauschenberg Photographs (New York: Pantheon, 1981), n.p.

- The first serial work Rauschenberg made was This Is the Outset Half of a Print Designed to Exist in Passing Fourth dimension (ca. 1949). Other examples include Cy + Roman Steps (I–Five) (1952), Automobile Tire Print (1953), Currents (1970), Hiccups (1978), The 1/iv Mile or 2 Furlong Piece (1981–98), and Synapsis Shuffle (1999). In add-on, the imagery that populates Rauschenberg's xxx-two-foot-long black-and-white silkscreen painting Barge (1962–63) also suggests, past its scroll-like format, that its imagery be read serially.

- Hopps, The Early 1950s, thirty.

- Rauschenberg steadfastly maintained that his sexual orientation was non the cornerstone upon which his art was fabricated. Even so, numerous scholars accept approached his piece of work from this angle. Meet, for instance, Jonathan D. Katz, "The Fine art of Lawmaking: Jasper Johns and Robert Rauschenberg," in Meaning Others: Creativity and Intimate Partnership, ed. Whitney Chadwick and Isabelle de Courtivron (London: Thames and Hudson, 1993), 189–207; Kenneth Eastward. Silver, "Modes of Disclosure: The Construction of Gay Identity and the Rise of Popular Art," in Hand-Painted Pop: American Fine art in Transition, 1955–61 (Los Angeles: Museum of Gimmicky Art, 1993), 179–203; Lisa Wainwright, "Reading Junk: Thematic Imagery in the Fine art of Robert Rauschenberg from 1952 to 1964" (PhD diss., Academy of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, 1993); Laura Auricchio, "Lifting the Veil: Robert Rauschenberg's Thirty-4 Drawings for Dante'due south Inferno and the Commercial Homoerotic Imagery of 1950s America," in "The Gay '90s: Disciplinary and Interdisciplinary Germination in Queer Studies," ed. Thomas Foster, Carol Siegel, and Ellen E. Berry, special consequence, Genders 26 (New York: New York University Printing, 1997): 119–54; and Tom Folland, "Robert Rauschenberg's Queer Modernism: The Early on Combines and Ornamentation," Art Bulletin 92, no. 4 (December 2010): 348–65.

- Circles and mirrors appear, for example, in Trinity (ca. 1949), Stone, Rock, Rock (ca. 1951), and Untitled [with collage and mirror] (ca. 1951). Notably, Stone, Stone, Stone also has a fragment of what appears to be a route map, possibly like to those used in Mother of God, collaged along its left side. In addition to these Parsons-era paintings, circles are much in prove in a number of works executed upon Rauschenberg'due south render to Blackness Mountain in 1951. See, for case, the Nighttime Blooming paintings (1951), the untitled sculpture fashioned from a Coke crate (1952), and a previously unknown painting whose composition is divided into eight vertical sections in which drawn circles populate all but the seventh section. (This work, a souvenir from Rauschenberg to Ben Shahn when they were both at Black Mountain in 1951, is now held by the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation.)

- Walter Hopps, unpublished interview with Lisa Wainwright, February 1992, Chicago.

- For an in-depth give-and-take of religious themes in Rauschenberg'due south early works, see Wainwright, "Resurrecting the Christian Rauschenberg," in "Reading Junk," 58–88, and Elizabeth Richards, "Rauschenberg's Religion: Autobiography and Spiritual Reference in Rauschenberg'due south Use of Textiles," Southeastern College Fine art Briefing Review xvi, no. 1 (2011): 39–48. Rose has stated that Rauschenberg's apply of Christian themes during this flow occurred because "he was worried well-nigh salvation. And indeed he always would be." Meet Barbara Rose, "Seeing Rauschenberg Seeing," Artforum 47, no. 1 (September 2008): 434.

Wainwright has identified religious references (either through the inclusion of printed texts or as compositional arrangements) on a number of Rauschenberg artworks, for instance,

Untitled [Christian symbol] (ca. 1952), Co-being (1961), Aenfloga (1961), and Franciscan II (Venetian) (1972). See Lisa Wainwright, "Rauschenberg's American Voodoo," New Art Examiner (May 1998): 28–33. Rauschenberg would occasionally return to bestowing suggestive religious titles on his artworks, for instance, Soles (1953), Hymnal (1955), and Chantry Peace Chile/ROCI Chile (1985), to name just a few. Robert S. Mattison has identified religious elements in two Combines: Odalisk (1955/1958), which includes a church envelope for donations and a printed reproduction of Christ as Noli me tangere; and Co-being (1961), which includes a saint'south molar reliquary. See Robert Saltonstall Mattison, Robert Rauschenberg: Breaking Boundaries (New Haven, CT: Yale University Printing, 2003), 62, 256.

Ironically, Rauschenberg was commissioned by the Vatican in 1996 to pigment an Apocalypse scene for the Aula liturgica di Padre Pio, a pilgrimage church designed past Renzo Pianoforte in the southern Italian town of San Giovanni Rotondo. Rauschenberg chose to depict God every bit a satellite dish, all knowing and all seeing; this deeply offended the Vatican, which ultimately rejected the piece of work. In 2005

The Happy Apocalypse was donated by the artist to the Menil Collection, a fitting home given Dominique de Menil'south commitment to sacred fine art in by and large secular environments. See Kate Bellin, "'What Were Halos?' The Dispute over Robert Rauschenberg's The Happy Apocalypse" (master's thesis, Christie's Education, New York, 2009). - Meet Mary Lynn Kotz, Rauschenberg, Fine art and Life (New York: Harry N. Abrams, 1990), 70.

- Robert Rauschenberg, unpublished interview with Walter Hopps, Jan 18–20, 1991.

- Roni Feinstein, "The Unknown Early Robert Rauschenberg: The Betty Parsons Exhibition of 1951," Arts Magazine 59, no. 5 (January 1985): 127.

- For two accounts of how Rauschenberg created this series, see Fielding Dawson quoted in Black Mountain College: Experiment in Art, ed. Vincent Katz (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 156, 158; and Hopps, The Early 1950s, 64. A Betty Parsons Gallery label on the reverse of one of the iii extant Nighttime Blooming paintings confirms that No. x, 1951 (a painting brought into the gallery for consignment, merely not part of the exhibition) was painted over. The repainted Night Blooming painting at present belongs to the Menil Drove, Houston. Encounter note 46 below.

- A facsimile of the handwritten letter, postmarked October 18, 1951, is reproduced in Hopps, The Early on 1950s, 230.

- Branden West. Joseph, Random Club: Robert Rauschenberg and the Neo-Avant-garde (Cambridge, MA: MIT Printing, 2003), 26. Joseph first explored this topic in his commodity "White on White," Critical Inquiry 27, no. ane (Autumn 2000): xc–121.

- Feinstein has linked this idea to "represent[ing] a conjoining of the banal (cartoons and roadmaps) with the elevated and sublime (allegory and spirituality), providing yet another note of irony." See Feinstein, "The Unknown Early Robert Rauschenberg," Arts Mag, 127.

- Joseph, Random Order, 315n14. In his text Joseph states: "In that location, Rauschenberg used a field of urban center maps to depict the earthly realm, employing collage as a means of directly incorporating elements of the exterior globe into the work and emphasizing their (and its) materiality." Run across Joseph, Random Social club, 26.

- Rosalind Krauss, "Rauschenberg and the Materialized Image," in Robert Rauschenberg, ed. Branden W. Joseph (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2002), 40.

- Roni Feinstein, "Random Order: The Starting time Fifteen Years of Robert Rauschenberg's Art, 1949–1964" (PhD diss., New York University, 1990), nine.

- Amid numerous references Rauschenberg made to this topic throughout his career, he said in 1966: "I didn't encounter Schwitters or Picasso until I had actually started working the manner I did." See Jeanne Siegal, Artwords: Discourse on the 60s and 70s (Ann Arbor, MI.: UMI Research Printing, 1985), 155.

- Kotz, Rauschenberg, Art and Life, 49. Rauschenberg must have as well learned to sew from his mother. He get-go studied fashion design at the Art Constitute of Kansas. During his matrimony he made all of Weil'southward dress, and a wedding ceremony dress he made for Ingeborg Lauterstein in 1950 was recently exhibited at Loretta Howard Gallery, New York, in Black Mountain College and Its Legacy (September 15–October 29, 2011). Rauschenberg would go on to design costumes for the Paul Taylor Dance Company, the Merce Cunningham Dance Visitor, and later Judson Trip the light fantastic Theater and the Trisha Brown Company, among others.

When Rauschenberg was kickoff living in New York, collage was much in evidence. Before going to Black Mountain, he may have visited the Museum of Modern Art'southward watershed exhibition

Collage (September 21–December five, 1948), which featured examples by Schwitters as well equally several Dada-period artworks by Max Ernst (1891–1976). The significance this exhibition may have had on Rauschenberg has been disregarded in the literature. During his brief marriage to Weil, Rauschenberg became familiar with the work of Joseph Cornell (1903–1972) through his in-laws' art drove and visiting Cornell exhibitions at Egan Gallery. Alan Solomon was the first to mention the importance of Schwitters in the catalogue accompanying Rauschenberg's first retrospective at the Jewish Museum in 1963, and Hopps has traced the importance of Schwitters, Cornell, and the Italian Alberto Burri on Rauschenberg's work in his Early 1950s catalogue. - Robert Rauschenberg quoted in Sam Hunter, Robert Rauschenberg: Works, Writings and Interviews (Barcelona: Ediciones Polígrafa, 2006), 24. For an investigation of Rauschenberg'southward employ of fabric as collage, see Wainwright, "Reading Junk" and Lisa Wainwright, "Robert Rauschenberg's Fabrics: Reconstructing Domestic Space" in Non at Dwelling: The Suppression of Domesticity in Modern Art and Compages, ed. Christopher Reed (London: Thames and Hudson, 1996): 193–205. Folland also quotes Rauschenberg's argument: "I'm an quondam collage man." Come across Folland, "Robert Rauschenberg'due south Queer Modernism," 356, 364n42. Rereading the proceedings of The Fine art of Aggregation, the 1961 symposium featuring Rauschenberg, Marcel Duchamp, Lawrence Alloway, Roger Shattuck, and Richard Huelsenbeck where that remark was made, it is articulate Rauschenberg was only referring to the fact that he had written notes for his talk on various scraps of newspaper, and was making a humorous quip, every bit was his manner. The temptation to elevate its importance, nevertheless, is understandable. See Folland, "Robert Rauschenberg's Queer Modernism," 348–65.

- The exhibition dates were May 14–June two, 1951.

- Robert Rauschenberg, telephone interview with Walter Hopps, August one, 1991.

- She connected: "Awful to piece of work at the League; couldn't store annihilation and we were always hauling things dorsum and forth. Bob hated leaving things around the League." See Weil, unpublished interview with Hopps, Jan 15, 1991. In the spiral text of his 1968 impress Autobiography, Rauschenberg wrote: "All-time work made at habitation."

- The checklist (with handwritten notations), the expenses, reviews, and the ledger book are in the Betty Parsons Papers, Athenaeum of American Art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.

- Mary Coles, "Bob Rauschenberg," Art Assimilate 25, no. 17 (June 1951), eighteen; Stuart Preston, "Varied Art Shown in Galleries Here," New York Times, May 18, 1951; and Dorothy Seckler, "Reviews and Previews: Robert Rauschenberg," ARTnews 50, no. 3 (May 1951): 59.

- Seckler, "Reviews and Previews," 59.

- Preston, "Varied Art Shown in Galleries Here." In the screw text of his 1968 impress Autobiography, Rauschenberg wrote of the Parsons exhibition: "First one man show Betty Parsons: paintings generally silver & wht. with cinematic composition. All paintings destroyed in ii accidental fires. . . ." Rauschenberg and Weil painted one wall of their apartment/studio in silver. As Weil recalled: "we painted a wall . . . with argent paint. . . . [W]e liked having that equally a . . . kind of intensive neutral [ground] to work on." See Weil, unpublished interview with Hopps, January 15, 1991. For Rauschenberg's account of the silver wall, come across Rose, "Seeing Rauschenberg Seeing," 45.

- It is non known where Siskind shot these photographs. Because the artworks appear to rest on a viewing ledge not unlike those institute in galleries, one can assume the location to be Betty Parsons Gallery. These photographs were first published in Feinstein, "The Unknown Early Robert Rauschenberg." Correspondence in the Betty Parsons Papers, Athenaeum of American Art, Smithsonian Establishment, Washington, D.C., indicates that Siskind reprinted the photos for the gallery in the early 1980s and that the gallery supplied copies to the artist.

- Gimmicky reviews of the Parsons exhibition say that information technology consisted of "13 oils" (confirmed by the printed checklist); in that location is no mention of sculptural work. Hopps may have "pushed" the artist to associate this championship with this sculpture, as witnessed by the author. This possibly hasty clan should therefore be reconsidered in light of the fact that both Rauschenberg and Weil separately referenced Rauschenberg's experiments with glass sculpture on Outer Island every bit well every bit his casting of sculptures in sand at Jones Beach for an Art Students League assignment. Man with Two Souls (perhaps made on this later occasion) has more in common with Greenhouse (ca. 1950)—another sculpture that contains various glass elements—than previously acknowledged in the literature. For more on Rauschenberg's early work in glass, meet Susan Weil, Oral History Interview with Karen Thomas, January 21, 2011. It is interesting to notation that Rauschenberg returned to working in glass late in his career. In 1997–98, he cast numerous glass sculptures based on objects that he had oft employed in his work, such equally the pillow and the automobile tire.

- This painting has nevertheless to exist directly associated with any of the twenty works known to exist in the gallery, and thus bears a descriptive championship. Its inclusion in the Parsons exhibition therefore has not been confirmed, although stylistically it is consistent with the works shown.

- Labels and/or markings on the contrary of all three works have clearly identified their original states: No. 1, 1951 (now known as Untitled [modest black painting], 1953) was given to John Cage at the time of the exhibition and is now in a private drove in Europe; Should Dearest Come First? (now known as Untitled [modest black painting], 1953) is in the collection of the Kunstmuseum Basel; and No. 10, 1951 (now known as Untitled [Nighttime Blooming series], ca. 1951) is in the Menil Drove, Houston. The identity of this terminal piece of work is noted here for the start fourth dimension. Until at present, it has been accepted that Rauschenberg repainted these Parsons works later his return from Europe in spring 1953 and not as early equally 1951 at Black Mountain. Obviously, he did non store all of the Parsons works with his friends and in-laws. Come across note 26 higher up.

- Gruen, "An Audience of One," 46.

- Ibid. This quote also appears in Feinstein, "The Unknown Early Robert Rauschenberg," 126.

- Rose, "Seeing Rauschenberg Seeing," 56. Mirrors were a consistent motif in Rauschenberg's art from this time forward.

- The details of this story take yet to be fully determined. Some accounts have Muzzle visiting the exhibition, making the quip well-nigh having no money, and receiving the gift from Parsons; other accounts identify Rauschenberg in the gallery when Muzzle visited and giving Cage the work himself. Rauschenberg has said that he met Cage at Blackness Mount in 1949 or 1950, but this is surely incorrect considering Cage was non teaching at that place in those years. For a recent restating of the story in an (unsuccessful) attempt at description, see Kay Larson, Where the Heart Beats: John Cage, Zen Buddhism, and the Inner Life of Artists (New York: Penguin, 2012), 227–35. Feinstein says that No. 1, 1951 was "a fetishistic piece of work that consisted of a hand outline, a leaf from a fortune teller's notebook, and a black arrow on a silver background" but offers no source for this data. See Feinstein, "Random Order," 72–73. While house-sitting for Cage in 1953, Rauschenberg painted the work black (as he would once again in 1985). The current possessor has confirmed the presence of pinkish under the black, but no silver. Run across email correspondence between the electric current owner and Paul Franklin, July vi, 2012, and July 12, 2012; copies in the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation athenaeum.

- This transaction is unsubstantiated and the author has been unable to admission the Leo Castelli Gallery Records, recently candy at the Archives of American Fine art, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C., to ostend.

- Seckler, "Reviews and Previews," 59.

- Rauschenberg, unpublished interview with Hopps, January eighteen–xx, 1991. The author was present during this commutation.

- Meet Roni Feinstein, "Robert Rauschenberg: Engaging the Everyday," in San Francisco Museum of Mod Art: 75 Years of Looking Forward , ed. Janet Bishop, Corey Keller, and Sarah Roberts (San Francisco: San Francisco Museum of Modernistic Fine art, 2009), 145–51. A complete exhibition history for Mother of God is available on the artwork's overview page.

- Frances Colpitt, "Rauschenberg: In the Kickoff," Art in America eighty, no. 4 (April 1992), 125.

- Roberta Smith, "Robert Rauschenberg, At Dwelling and Away," New York Times, August 6, 1991.

- Fred Camper, "The Unordered Universe," Chicago Reader, March 26–Apr ane, 1992, 31.

Download PDF

Photo courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

Photo courtesy the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York

0 Response to "Kenneth E Silver ââåmodes of Disclosure the Construction of Gay Identity and the Rise of Pop Art"

Post a Comment